| 28 April 2003 This lecture covers the reading in Chapter 7: Methods and Classes (continued) |

Overloading a method

Passing Arguments By Value and Reference Nested and inner classes |

Sometimes it is convenient to have one name for something even it takes

several slightly different forms.

For example, we say "drive" a motocycle and "drive" a car, even though someone

who can drive a car does not necessarily know how to drive a motorcycle.

The drive method has a different form for motorcycles than for cars.

The English word "drive" is polymorphic, and means a different form of driving,

depending on the type of vehicle.

Similarly, we can "greet" a friend in a different form than we "greet" the

Queen of England.

It makes our language more simple when we can use the same word for closely

related forms.

Otherwise, we would have to have many more words, and that would be

inconvenient.

Java has its counterpart to this flexibility of natural language.

The compiler looks for the "signature" of a method. Multiple methods can have

the same method name, and yet have different signatures.

For example:

We say that myMethod() is overloaded, and has four signatures.

A signature consists of a number of parameters and their types.

Therefore, a method with one argument can have multiple signatures with one

argument if that argument has a different data type for each signature.

Indeed, we can say that a given method can have multiple forms. Overloading

is an example of polymorphism.

Because a single class can have one or more overloaded methods, overloading

helps make it practical to have encapsulation by class.

Every instance of a class--that is, every object--inherits all the

properties and methods of that class, including any overloaded methods.

The output is:

No parameters b: true a: 10 a and b: 10 20 double a: 2.1 Result of ob.test(2.1): 4.41

If you do not define any constructor(s) for a class, Java automatically

provides a default constructor that has no arguments.

However, if you define any constructor(s) for a class, then you must define them

all, and Java provides no default constructor.

The output is:

ob1 == ob2: false

Let's review two examples of using

constructors to create box objects.

The flexibility of polymorphism often appears as a series of overloaded

constructors.

The output is:

name=Harry,id=2125,salary=40000.0 name=Employee #2126,id=2126,salary=60000.0 name=Mary,id=2127,salary=80000.9 name=,id=2128,salary=0.0 name=Employee #2129,id=2129,salary=68888.0

Earlier, we saw an example that compared two string objects:

http://www.wordesign.com/java/edp306704/session3.htm#comparing_objects

There, we used the equals() method and pass it a parameter that was a reference

to a string object.

Here's another example in which we pass an object as a parameter, but this time,

it is a parameter to a constructor.

The output is:

ob1 == ob2: true ob1 == ob3: false ob3 == ob4: true

The following example has two constructors that take a single argument. Which are the lines the code that call these two constructors, and how does the javac compiler know the difference between the two constructors?

The output is:

Volume of mybox1 is 3000.0 Volume of mybox2 is -1.0 Volume of cube is 343.0 Volume of clone is 3000.0

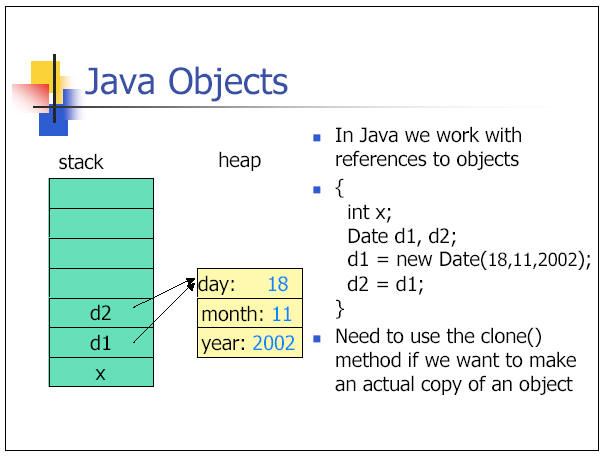

In this section, we compare calling by value, which is for primitives, to calling by reference, which is for objects.

The output is:

a and b before call: 15 20 a and b after call: 15 20

Even though line 21 calls the meth() method, the result of lines 23-24 so that these lines see the same values as those declared in line 16.

However, an object has, if you will, a history or a "state" of existence than a primitive does not have.

The output is:

ob.a and ob.b before call: 15 20 ob.a and ob.b after call: 30 10

Calling the constructor in line 24 passes in values that get assigned to a

and b in lines 8-9.

However, in this example, a and b are not just integers: they are fields of an

object.

Therefore, the logic of lines 15-16 operates on data belonging to an object of

type test called

o.

An object is similar to a data type, that is, a custom data type. Therefore, it might not be surprising that it is possible for a method to accept as a parameter something that is an object (previous example, line 29). Similarly, an object can also be the return value of a method. Let's see.

The output is:

ob1.a: 2 ob2.a: 12 ob2.a after second increase: 22

The output is:

Factorial of 1 is 1 Factorial of 2 is 2 Factorial of 3 is 6 Factorial of 4 is 24 Factorial of 5 is 120

A recursive method is a method that calls itself. For example, a method that calls itself upon the previous result of calling itself. Factorial: 5! = 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1. Note that factorial 0 = 1 by definition. public class MathUtil { /** * This method computes the factorial of a number, the algorithm * defined as: factorial(N) = N * (factorial(N-1) if N > 1, * if N is 1 or less, the value of the factorial is 1. * * @param number the number for which to compute the factorial * product. * @return returns the factorial of a given number. */ public static int calculateFactorial(int number) { // this is the blocking test, this test is used to stop the // recursion, without this test, we would have an infinite // recursion. if (number > 1) { // we make a recursive call to compute the factorial return number * calculateFactorial(number -1); } else { return 1; } } }

Notes:

Recursive algorithms execute slower than non-recursive algorithms because each method call has some overhead. However, it can be much quicker and easier to write a method recursively. Nowadays, programmer time is more expensive than CPU time, so recursion has its place.

Recursive and non-recursive algorithms equivalent in functionality. You can attain the same functionality recursive and non-recursive algorithms.

Certain programmers consider recursive algorithms to be an elegant way to break a complex problem into smaller pieces.

The output is:

[0] 0 [1] 1 [2] 2 [3] 3 [4] 4 [5] 5 [6] 6 [7] 7 [8] 8 [9] 9

This material is theoretical and will not be on the final exam.

Question: Why is it possible for a recursive method to cause the stack to overrun?

The output is:

a, b, and c: 10 20 100

http://java.sun.com/docs/books/tutorial/java/javaOO/accesscontrol.html

One of the benefits of classes is that classes can protect their member variables and methods from access by other objects. Why is this important? Well, consider this. You're writing a class that represents a query on a database that contains all kinds of secret information, say employee records or income statements for your startup company.

Certain information and queries contained in the class, the ones supported by the publicly accessible methods and variables in your query object, are OK for the consumption of any other object in the system. Other queries contained in the class are there simply for the personal use of the class. They support the operation of the class but should not be used by objects of another type--you've got secret information to protect. You'd like to be able to protect these personal variables and methods at the language level and disallow access by objects of another type.

In Java, you can use access specifiers to protect both a class's variables and its methods when you declare them. The Java language supports four distinct access levels for member variables and methods: private, protected, public, and, if left unspecified, package.

The following chart shows the access level permitted by each specifier.

Specifier class subclass package world privateX protectedX X* X publicX X X X packageX X The first column indicates whether the class itself has access to the member defined by the access specifier. As you can see, a class always has access to its own members. The second column indicates whether subclasses of the class (regardless of which package they are in) have access to the member. The third column indicates whether classes in the same package as the class (regardless of their parentage) have access to the member. The fourth column indicates whether all classes have access to the member.

Note that the protected/subclass intersection has an '*' . This particular access case has a special caveat discussed in detail later.

Let's look at each access level in more detail.

The most restrictive access level is private. A private member is accessible only to the class in which it is defined. Use this access to declare members that should only be used by the class. This includes variables that contain information that if accessed by an outsider could put the object in an inconsistent state, or methods that, if invoked by an outsider, could jeopardize the state of the object or the program in which it's running. Private members are like secrets you never tell anybody.

To declare a private member, use the

privatekeyword in its declaration. The following class contains one private member variable and one private method:class Alpha { private int iamprivate; private void privateMethod() { System.out.println("privateMethod"); } }Objects of type

Alphacan inspect or modify theiamprivatevariable and can invokeprivateMethod, but objects of other types cannot. For example, theBetaclass defined here:class Beta { void accessMethod() { Alpha a = new Alpha(); a.iamprivate = 10; // illegal a.privateMethod(); // illegal } }cannot access the

iamprivatevariable or invokeprivateMethodon an object of typeAlphabecauseBetais not of typeAlpha.When one of your classes is attempting to access a member varible to which it does not have access, the compiler prints an error message similar to the following and refuses to compile your program:

Beta.java:9: Variable iamprivate in class Alpha not accessible from class Beta. a.iamprivate = 10; // illegal ^ 1 errorAlso, if your program is attempting to access a method to which it does not have access, you will see a compiler error like this:

Beta.java:12: No method matching privateMethod() found in class Alpha. a.privateMethod(); // illegal 1 errorNew Java programmers might ask if one

Alphaobject can access the private members of anotherAlphaobject. This is illustrated by the following example. Suppose theAlphaclass contained an instance method that compared the currentAlphaobject (this) to another object based on theiriamprivatevariables:class Alpha { private int iamprivate; boolean isEqualTo(Alpha anotherAlpha) { if (this.iamprivate == anotherAlpha.iamprivate) return true; else return false; } }This is perfectly legal. Objects of the same type have access to one another's private members. This is because access restrictions apply at the class or type level (all instances of a class) rather than at the object level (this particular instance of a class).

Note:

thisis a Java language keyword that refers to the current object. For more information about how to usethissee The Method Body.

The next access level specifier is protected, which allows the class itself, subclasses (with the caveat that we referred to earlier), and all classes in the same package to access the members. Use the protected access level when it's appropriate for a class's subclasses to have access to the member, but not unrelated classes. Protected members are like family secrets--you don't mind if the whole family knows, and even a few trusted friends but you wouldn't want any outsiders to know.

To declare a protected member, use the keyword

protected. First, let's look at how the protected specifier affects access for classes in the same package. Consider this version of theAlphaclass which is now declared to be within a package namedGreekand which has one protected member variable and one protected method declared in it:package Greek; public class Alpha { protected int iamprotected; protected void protectedMethod() { System.out.println("protectedMethod"); } }Now, suppose that the class

Gammawas also declared to be a member of theGreekpackage (and is not a subclass ofAlpha). TheGammaclass can legally access anAlphaobject'siamprotectedmember variable and can legally invoke itsprotectedMethod:package Greek; class Gamma { void accessMethod() { Alpha a = new Alpha(); a.iamprotected = 10; // legal a.protectedMethod(); // legal } }That's pretty straightforward. Now, let's investigate how the

protectedspecifier affects access for subclasses ofAlpha.Let's introduce a new class,

Delta, that derives fromAlphabut lives in a different package--Latin. TheDeltaclass can access bothiamprotectedandprotectedMethod, but only on objects of typeDeltaor its subclasses. TheDeltaclass cannot accessiamprotectedorprotectedMethodon objects of typeAlpha.accessMethodin the following code sample attempts to access theiamprotectedmember variable on an object of typeAlpha, which is illegal, and on an object of typeDelta, which is legal. Similarly,accessMethodattempts to invoke anAlphaobject'sprotectedMethodwhich is also illegal:package Latin; import Greek.*; class Delta extends Alpha { void accessMethod(Alpha a, Delta d) { a.iamprotected = 10; // illegal d.iamprotected = 10; // legal a.protectedMethod(); // illegal d.protectedMethod(); // legal } }If a class is both a subclass of and in the same package as the class with the protected member, then the class has access to the protected member.

The easiest access specifier is

public. Any class, in any package, has access to a class's public members. Declare public members only if such access cannot produce undesirable results if an outsider uses them. There are no personal or family secrets here; this is for stuff you don't mind anybody else knowing.To declare a public member, use the keyword

public. For example,package Greek; public class Alpha { public int iampublic; public void publicMethod() { System.out.println("publicMethod"); } }Let's rewrite our

Betaclass one more time and put it in a different package thanAlphaand make sure that it is completely unrelated to (not a subclass of)Alpha:package Roman; import Greek.*; class Beta { void accessMethod() { Alpha a = new Alpha(); a.iampublic = 10; // legal a.publicMethod(); // legal } }As you can see from the above code snippet,

Betacan legally inspect and modify theiampublicvariable in theAlphaclass and can legally invokepublicMethod.

The package access level is what you get if you don't explicitly set a member's access to one of the other levels. This access level allows classes in the same package as your class to access the members. This level of access assumes that classes in the same package are trusted friends. This level of trust is like that which you extend to your closest friends but wouldn't trust even to your family.

For example, this version of the

Alphaclass declares a single package-access member variable and a single package-access method.Alphalives in theGreekpackage:package Greek; class Alpha { int iampackage; void packageMethod() { System.out.println("packageMethod"); } }The

Alphaclass has access both toiampackageandpackageMethod. In addition, all the classes declared within the same package as Alpha also have access toiampackageandpackageMethod. Suppose that bothAlphaandBetawere declared as part of theGreekpackage:package Greek; class Beta { void accessMethod() { Alpha a = new Alpha(); a.iampackage = 10; // legal a.packageMethod(); // legal } }

Betacan legally accessiampackageandpackageMethodas shown.

The output is:

Stack in mystack1: 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Stack in mystack2: 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10

The modifier keywords include

http://java.sun.com/docs/books/tutorial/reflect/class/getModifiers.html

The HelloWorld.java program is the first place we saw the keyword static.

The main() method must be static because the Java Virtual Machine needs to call

it BEFORE any objects exist.

If a class has a static member (variable or method), then that method is

independent of an object.

Static members exist before the coming and going of objects. In the sense of

their always being there, they are standing or static.

Static members are efficient for memory: there is only one copy, no matter how

many objects exists.

The output is:

a = 42 b = 99

The output is:

Starting with 0 instances Created 10 instances

http://java.sun.com/docs/books/tutorial/java/nutsandbolts/finalVariables.html

A constant variable is a variable which is assigned a value once and cannot be changed afterward (during execution of the program). The compiler optimizes a constant for memory storage and performance.

Examples of constants

You can declare a variable in any scope to be final

. The value of a final variable cannot change after it has been initialized. Such variables are similar to constants in other programming languages.

To declare a final variable, use the

finalkeyword in the variable declaration before the type:final int aFinalVar = 0;The previous statement declares a final variable and initializes it, all at once. Subsequent attempts to assign a value to

aFinalVarresult in a compiler error. You may, if necessary, defer initialization of a final local variable. Simply declare the local variable and initialize it later, like this:final int blankfinal; . . . blankfinal = 0;A final local variable that has been declared but not yet initialized is called a blank final. Again, once a final local variable has been initialized, it cannot be set, and any later attempts to assign a value to

blankfinalresult in a compile-time error.

http://java.sun.com/docs/books/tutorial/java/javaOO/final.html

There is something funny about arrays... they are implemented as objects!

Every instance of the Array class has a property called length.

The length of an array is NOT necessarily the current count of elements.

The length of an array is the total possible memory slots (elements) available

for holding values or objects.

We will not need to learn about this unless we study applets.

The output is:

D:\java\teachjava\spring2003\session7>java StringDemo First String Second String First String and Second String D:\java\teachjava\spring2003\session7>java StringDemo2 Length of strOb1: 12 Char at index 3 in strOb1: s strOb1 != strOb2 strOb1 == strOb3

The output is:

args[0]: sky args[1]: is args[2]: blue args[3]: 4 args[4]: you

Write a program that exercises your knowledge and research of Strings and arrays. Your program should also use access control and involve the use of one or more methods that use an object as an argument and/or a return value.

______________

course

homepage course

calendar